Cellulose or plastic? It’s not just about shopping bags

![]()

![]() The vast product arrays that move through modern storage warehouses provide a constant challenge to owners, insurers, and code officials to assure the built-in fire protection is suitable to protect the hazards. The combustibility and heat release rate of products in a warehouse today might differ dramatically from those that were there not long before.

The vast product arrays that move through modern storage warehouses provide a constant challenge to owners, insurers, and code officials to assure the built-in fire protection is suitable to protect the hazards. The combustibility and heat release rate of products in a warehouse today might differ dramatically from those that were there not long before.

As markets adapt to satisfy changing customer needs, products may be modified in ways that affect their fire performance. For example, changing television cases from metal to polycarbonate resins may lessen their weight, but increase their combustibility.

Likewise, packaging techniques to protect an item from damage during shipping or handling may vary with the addition of Group A plastics instead of less combustible shredded paper or cardboard.

There is yet another element that changes how commodities may need to be protected in warehouse storage: the pallet(s) that are used to aid in materials handling. Pallets generally are made from wood or wood by-products, plastic, wood-plastic composite, or, in some cases, metal. They come in a variety of configurations that may be matched specifically to the products being stored. In all cases, the pallets’ purpose is to make materials handling easy and efficient.

The use of some plastic pallets may have significant consequences on the fire protection design for the storage array: in some cases, the commodity hazard classification may have to be increased by two classes to assure adequate fire sprinkler protection is provided.

Wood or plastic: Is one better?

The longstanding predominance of wood pallets in storage arrays is being challenged by the use of synthetic materials such as high-density polyethylene (HDPE), polypropylene (PP), polyvinylchloride (PVC) and fiber-reinforced low-density polymers such as expanded polystyrene (EPS). Wood pallets typically are manufactured from various types of hardwoods (e.g., oak, yellow poplar, and alder) and softwoods (e.g., pine).

While the initial investment in plastic pallets costs more than wood, plastic pallets are more resistant to weather, oil, and chemical attack, and damage from rough handling. In addition to their durability, plastic pallets are easier to clean – an important consideration where hygiene is important such as in food or pharmaceutical storage – and they do not absorb water.

Plastic pallets can be lightweight and easily moved which can result in fewer lifting-related back and shoulder injuries. Plastic pallets do not include nails, splinters, or wooden shavings that can damage the product or injure an employee. Like a wood pallet, plastic pallets can be recycled at the end of their useful life.

Plastic pallets usually are injection molded. Most injection molding is done using virgin or high-quality reprocessed resin. The resin is heated and flows into a mold that provides the pallet’s final shape and features such as an open-cell deck, structural support, and openings where handling apparatus (forklifts and other powered industrial trucks) can lift the pallet. Injection molding is expensive, but it’s also the highest speed production process. Pallets can be made very quickly once the mold design is finalized.

Structural foam molding is another process that is widely used for manufacturing plastic pallets because it costs less than injection molding while offering many of the same benefits. Structural foam is manufactured under lower pressure than injection molding, and uses gas in the process, rendering the inside of the plastic part porous instead of solid. This porosity allows for more rigid platforms making structural foam a good option for ensuring high weight capacity in racking. The trade-off is that the porosity renders the plastic more susceptible to damage at impact. (Trebilcock, B., 2010) Furthermore, the porosity increases the combustibility due to lower physical density and entrained air in the plastic structure.

Plastic pallets may burn as hot as wood and for a longer time. When burning, plastic pallets may melt, drip, and form pools of liquid plastic on floors. Burning pools of plastic can flow and spread fire to other areas of a facility.

Furthermore, according to the Inland Marine Underwriters Association, a not-for-profit insurance organization:

- The time it takes for a fire to spread to a pallet above an ignited pallet is around 18 minutes for plastic pallets and nearly 50 minutes for wooden ones.

- Large fires involving plastic pallets create large amounts of black smoke that is not only more toxic but can significantly hinder firefighting.

- Flames from wooden pallets are almost entirely confined to the height of the stack and are seldom higher than 1 m (3 feet) while those from plastic pallets far exceeded the stack heights and can reach in excess of 6 m (20 feet).

- Plastic pallets are easily ignited by a match whereas wooden pallets required a far more energetic fuel source. (IMUA, 2010).

Wood or plastic: Fire protection

Fire protection standards for storage arrays have been developed over the years based on the ordinary combustible characteristics that wood pallets add to a commodity, especially in a rack, palletized, or shelf storage configurations. The research data is used to develop fire safety standards and insurance regulations that provide reasonable levels of protection and loss mitigation.

Chapter 32 of the International Fire Code (IFC) – which establishes requirements for high-piled storage – refers to NFPA 13, Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems for design and installation criteria to protect high-piled storage arrays. For years, fire tests were based on wood pallets as part of the unit load, and they were considered no more hazardous than ordinary combustibles. The advent of plastics in materials handling changed the fire protection threat and fire protection design criteria. In order to protect commodities on plastic pallets, sprinkler coverage and placement, design density, pipe sizes, and water supplies may have to be altered.

Recognizing the potential increased fire hazard associated with plastic pallets, FM Approvals (a member of the FM Global Group) developed Approval Standard 4996 for the “Classification of Pallets and Other Material Handling Products as Equivalent to Wood Pallets” and Underwriters Laboratories published UL 2335 “Fire Tests of Storage Pallets.”

FM tests eight stacks of pallets that are out 1.2 m (4 feet) high. Special water-application nozzles are placed in a grid pattern of about 204 mm (8 inches) above the pallet stacks. The fire is started with four gasoline-soaked igniters.

To successfully pass the FM test for the plastic pallets to be considered equivalent to wood, the fire must be controlled when the water application density of 5.9 mm/min (0.15 GPM/ft2) is applied within the 10-minute test time frame. (FM Approvals, 2013). Application density is the key to successful fire outcomes: the amount of water applied to a fire must be capable of absorbing the heat output.

UL 2335 consists of two fire-performance tests: an idle pallet storage test and a commodity storage test. The idle pallet test involves burning six 4-m (12-ft)-high stacks of pallets beneath a sprinklered ceiling. Test parameters are the number of sprinklers activated, stack stability, time for the fire to extend to the end of the array, and maximum temperature of a steel beam over the fire. The commodity storage test uses a calorimeter to measure heat release from burning pallets loaded with Class II commodities such as bottles of non-flammable liquids or non-combustible foods stored in paper or wooden containers. (UL, 2012)

The International Fire Code permits pallets that are listed and labeled in accordance with FM 4996 or UL 2335 to be treated as wood pallets for determining fire sprinkler design requirements.

Plastic pallet consequences

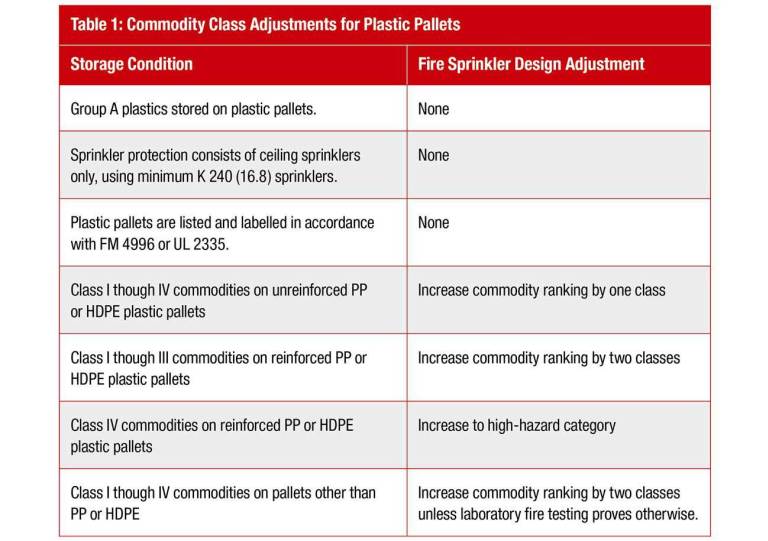

The code official, owner, insurer, and fire protection contractor must take special care to understand the impact that plastic pallets may have on the fire sprinkler system design, Table 1 summarizes the requirements from IFC Chapter 32:

As an example, imagine a storage array consisting of appliances such as stoves and refrigerators in single-thickness cardboard cartons on double-row racks 6 m (20 feet) high. Aisles are 2.4 m (8 feet) wide and there are no in-rack sprinklers: a common scenario in big-box retail applications. Historically, the products have been strapped on to wood pallets for easy maneuvering onto the racks and throughout the store. An analysis of this commodity results in it being classified as a Class II commodity.

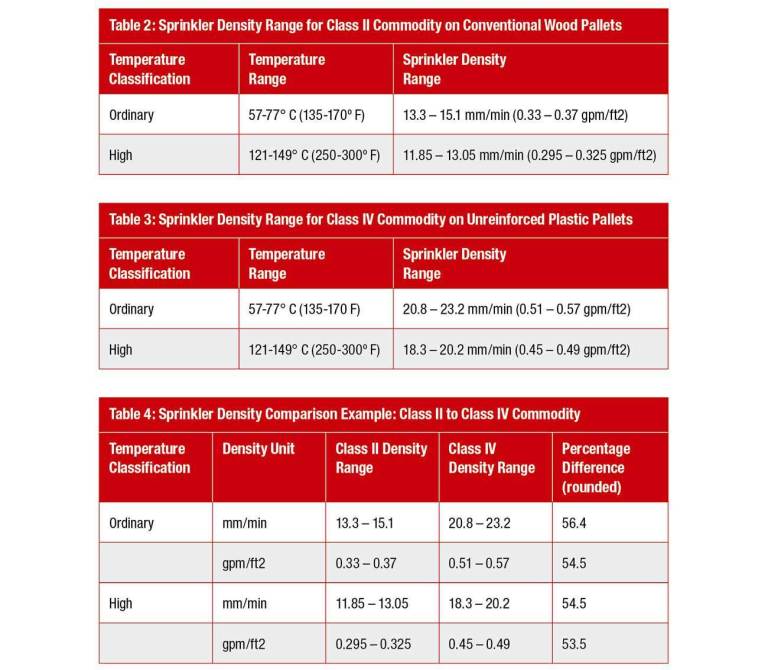

NFPA 13 Table 16.2.1.3.2 allows this configuration to be protected by ceiling sprinklers only. Table 2 provides a range of sprinkler discharge density needed to protect this storage array.

Imagine changing the material handling to unlisted, reinforced plastic pallets. IFC 3203.10.2 would require an increase of two hazard classes to protect this new configuration. What does that do to the required fire sprinkler density range? Table 3 provides the answer:

Finally, Table 4 compares the differences in sprinkler density demand for the two scenarios.

All this number crunching brings us to one conclusion: by changing from wood to unreinforced plastic pallets, to control a fire with the new packaging the sprinkler system would have to deliver about 55% more water than its initial design requirement.

Summary

Plastics have changed the world in which we live: they have provided us shipping and packaging solutions that a generation ago would have been considered fantastic. The rapid pace of change has brought its share of challenges as well. Owners, insurers, code officials and fire protection contractors must educate themselves to the challenges of protecting these materials through sound scientific and engineering principles.

For more information, go to codes.iccsafe.org.

References

- FM Approvals (August, 2013). “Approval Standard for Classification of Pallets and Other Material Handling Products as Equivalent to Wood Pallets”.

- Inland Marine Underwriters Association (IMUA) Loss Control and Claims Committee (October, 2010). “Pallets.” Retrieved from http://www.imua.org/Files/reports/999173.html

- Trebilcock, B. (July 27, 2010) “Plastic Pallets 101”. Modern Materials Handling. Retrieved from http://www.mmh.com/article/plastic_pallets_101

- Underwriters Laboratories (2012). “Fire Tests of Storage Pallets”.

This article first appeared in the March 2018 issue of International Fire Protection magazine and is reproduced by permission of MDM Publishing Ltd.