The Practicality of the I-Joist as a Ceiling Joist

Here we spoke with experts in the field to determine if I-joists can be used as ceiling joists

The engineered wood joist, more commonly known as an I-joist, is a product designed to eliminate span limits that often occur with conventional wood joists. Invented in 1969, the I-joist has considerable strength in relation to its size and weight.

I-joists enable framers to design expansive indoor spaces without the need for walls or columns. Their production involves combining sawdust or wood scraps with adhesive to create strong panels, which are then laminated under pressure to top and bottom cords using additional glue. This engineered construction minimizes shrinkage, twisting and other issues commonly associated with drying lumber, delivering quieter, flatter, and longer-lasting surfaces.

Despite the advantages of I-joists, when used as ceiling joists, they need some help. I’ve authored a half-dozen or so wood framing articles, so the practicality of the I-joist as a ceiling joist sometimes nibbles at my few remaining brain cells. As I see it, the ceiling joist acts as a tension member. My May 2018 Building Safety Journal article on rafter and ceiling joist framing explains this. You can read the article here.

One day, I decided to go to the crux of the matter and find the answer to the question, ‘Will I-joists work as ceiling joists?’

Insights from Experts and Practical Lessons on I-joists

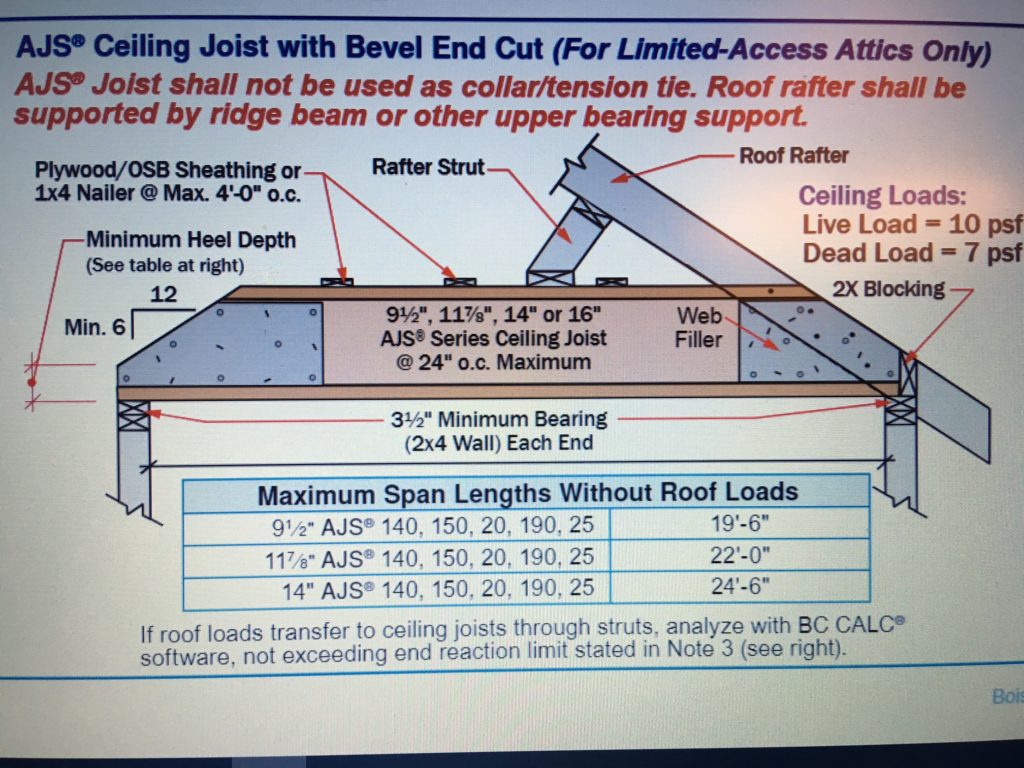

Boise-Cascade and Weyerhaeuser, two of the largest companies, provide plenty of data on I-joists. Boise-Cascade says they are not meant for service as a ceiling joist (tension tie) without special engineering. This clearly appears on the company’s installation guide in bold, red print.

As for Weyerhaeuser, Product Support Engineer Jason Shumaker, P.E., agreed with his company’s literature in an email, “…when the ceiling joists are being used as tension ties to keep the rafters from spreading… the connection from the I-joist to the rafter… would need to be designed by the EOR/AOR [engineer of record/architect of record].”

Most other I-joist manufacturers provide similar information, typically available on their company websites. In the past, I would ask the contractor to provide a copy of the guidelines, but I quickly realized I could achieve faster and more reliable results by going straight to the source. Plus, this approach eliminates any chance of miscommunication.

To complete my education, I spoke with Lars Jensen, P.E., a structural engineer based in Cape Cod who presents regularly to inspector groups in Massachusetts, who hammered home the final nail for me. “I-joists are generally not a good member to use for tension ties,” he said, “because the force typically comes into the member through the thin web, and they (manufacturers) are probably and rightfully worried about proper load entry, even if the web is fully packed,” he shared.

Thin web? I hurried through my notes. I noticed that Shumaker had also told me that in this configuration, laminated veneer lumber works better than I-joists as the connection capacity is easier to achieve. Both engineers had mentioned the need for a professional engineer’s review.

When I heard from Jensen and then looked at my notes, I knew I had passed the finish line.

These days, before I sign off on a framing inspection, all the I-joists used in a rafter-tension tie assembly require an installation as shown in the manufacturer’s guidelines, along with the stamp of a registered professional engineer.

For more product evaluation and testing services, visit the International Code Council’s dedicated webpage here.